An ode to no-nonsense autism dad @autismhoodjay

By Jill Escher

As fairy tales about autism sweep across social media — autism is a “superpower,” autism is just a “type of normal brain” — I wish to express gratitude for one of my favorite tellers of autism truths, a single dad on Twitter who goes by the handle @autismhoodjay. Jay (really Jason) lives in the raw and ragged reality of autism, and fearlessly punches back at ivory tower ideology and online neuro-bullies. With tweets that burst with love for, and panic about, his 10 year-old son Seamus, Jay is a mix of funny, poetic, poignant, philosophical, and scathing.

As his profile says, ”I'm a single dad, my son is autistic, ADHD, epileptic, I tweet what I want when I want…”

Apart from the fact that his refreshingly blunt tweets inject sanity into my Twitter feed, I don’t know much about Jay. But I can glean that he has a job cleaning offices near his apartment, walks with Seamus 22 blocks to the pharmacy to pick up his epilepsy medication, sometimes struggles to pay the rent, and provides all the Paw Patrol paraphernalia an autistic boy could want. It’s an isolating and often exhausting life, haunted by a gnawing dread about the future. I think he speaks for most autism parents with this lament:

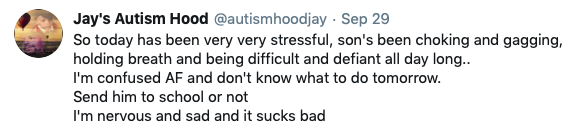

But forget the long-term, today’s daily struggles can also be overwhelming. Jay is unafraid to say that autism life can hurt:

When neurodiversity trolls castigate him for choosing to give Seamus therapy (not event ABA therapy, because “I can’t afford that shit, and insurance won’t pay”), Jay shoots back with a sentiment I know many of us have felt:

He also points out the obvious: the trolls aren’t parenting kids with severe autism, and have never walked an inch in Jay’s shoes, or felt his dread.

In a recent video he explains his desperation to prevent all-too-possible disasters that befall autistic people who do not understand rules: https://twitter.com/autismhoodjay/status/1179750307703803904?s=20. He knows Seamus is liable to “end up in the detention hall, or jail or prison… or some rogue-ass cop (could) decide to blow his head off because he don’t understand the rules.” Those who dog-pile on him inhabit an autism fantasy world divorced from the sweat and tears of severe mental disorder, and have the cognitive luxury of trading barbs on social media. “I live in the real world, the real world, not the old fake-ass Twitter world,” he retorts.

Jay also explains to his detractors how his fears for his son are compounded by racism. “My son is mixed, he’s a kid of color. It will break my heart for my son to do something that he doesn’t think is wrong, and it obviously is, and get thrown into a detention hall with a bunch of dope boys or criminals, or some racist cop blows his head off…. This is the kind of shit I worry about, as a black man in America with a kid of color, this is the kind of thing I worry about every goddamn day. And that’s my reality. It might not be yours, but that’s my reality. There’s certain things in this world that this dude has to understand….. People out here have… no clue what autism is. All they just see is a little kid of color acting up doing shit, they don’t know he’s autistic, they don’t know, they just don’t.”

(By the way, expletives are part of the Jay way.)

And now for something else we to which we can all relate:

Hahaha, took the words out of my mouth, but said much better!

You have to love Jay for calling BS on the over-broad autism spectrum, which throws together quirky and capable people with those clearly functionally disabled like his son.

(smh = shaking my head). How many people here wish Jay served on a DSM-5 revision committee? Heck, we would be better off with him in charge than our disgraceful status quo.

Jay knows exactly what’s a stake. A realistic societal understanding of autism that adjusts policies and funding to meet the very urgent needs:

And he defends proper use of the English language to reflect, not obfuscate, reality… because his son is indeed low functioning and disabled. There’s much utility and no shame in using objectively accurate descriptors:

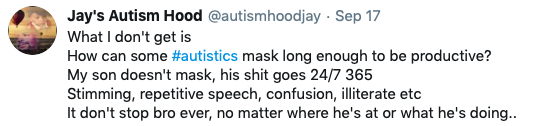

Jay scoffs at the idea that a person with autism can “mask” their impairments, since in the Autism Hood disability never takes a break:

When Seamus started having seizures two months ago, you could see all hell breaking loose in their already fragile lives:

It felt like the trials of Job, autism style. Where will it end? What other shoe will drop? The Autism Hood may be a place of love, but things can get seriously rough, and sometimes you wish you could teleport over there to help him out.

Whether you want to pray for Jay, admire his anti-troll judo moves, or just bask in some refreshing, yet always affectionate, authenticity about autism, visit Jay’s Autism Hood here.

Jill Escher is president of National Council on Severe Autism. You can find her on Twitter at @jillescher.