By Jackie Kancir, NCSA Executive Director

____________________________________

This is not a story about a doll. This is about how autism has been rebranded, monetized, and flattened into something safe for public consumption while the people with the highest needs remain excluded from public life, public policy, and public concern.

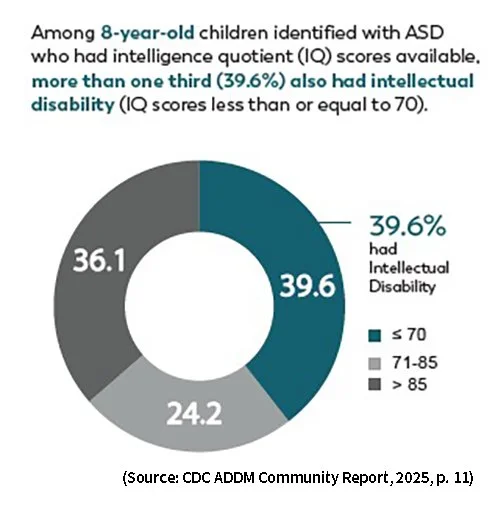

According to the most recent CDC ADDM data, among eight-year-old children identified with autism who had IQ data available, 39.6% had co-occurring intellectual disability (ID), defined as an IQ of 70 or below. An additional 24.2% fell in the borderline range, with IQ scores between 71 and 85. Only 36.1% had IQs above 85 (CDC ADDM Community Report, 2025, p. 11).

Therefore, nearly two-thirds of autistic children have cognitive impairment. These individuals do not represent an edge case. They constitute the majority of the autistic population.

Nevertheless, the version of autism presented to the public through toys, marketing, and media overwhelmingly reflects the smallest and most advantaged segment. This portrayal is tech savvy, functionally typical, cognitively gifted, emotionally legible, and socially palatable. It reassures the public that autism is manageable, tidy, and compatible with existing social norms.

That marketed narrative aligns neatly with approximately 36 percent of autistic people. It excludes the remaining 64 percent.

For individuals with intellectual disability or borderline ID, autism is not simply a different way of being. It is a lifelong condition that often requires constant supervision, comprehensive supports, and sustained public investment. Many will never live independently. Many cannot reliably self-advocate, even with assistive communication technology. Their lives are shaped not by identity language but by access to care, staffing, housing, and safety.

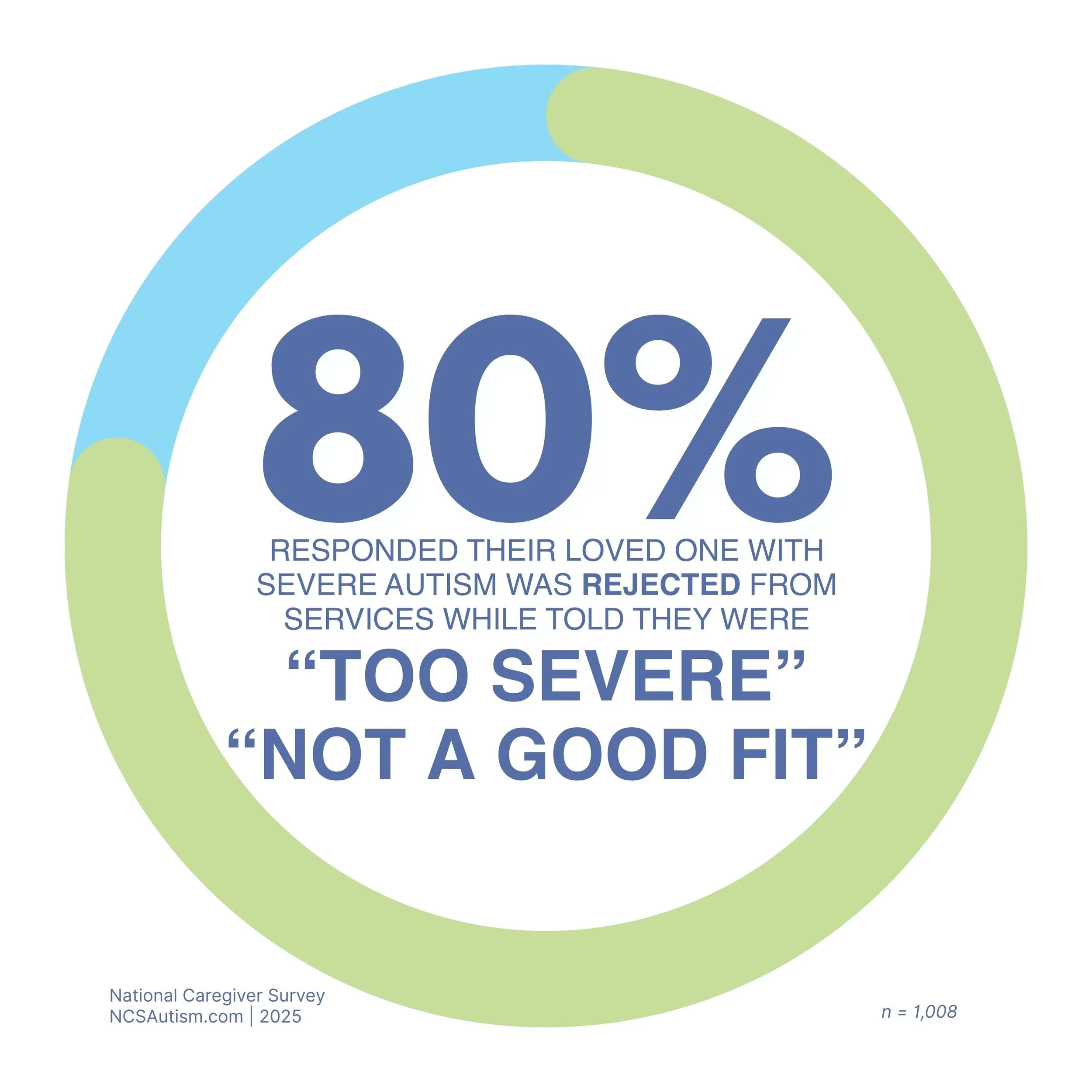

The 2025 national caregiver survey by NCSA found that 80% of those with severe forms of autism have been denied access to disability services explicitly because they were deemed “too severe.” Only 21% have reliable direct support staffing. Housing instability is widespread, and long-term planning remains a crisis for families aging alongside their disabled children.

Many in this population are left languishing without a single friend outside their immediate family. However, these realities do not appear in celebratory “diversity” campaigns. They do not translate easily into merchandise. They are fundamentally incompatible with narratives that frame autism primarily as a cultural identity rather than a disabling condition.

I am always taken aback when I see words like “diversity” being used in the context of “assimilation.” The term diversity would indicate variability, not sameness. So why do diversity celebration campaigns so routinely convey the message: “We’re just like everyone else”? How can anyone celebrate what cannot even be acknowledged?

Children learn social meaning through play. Toys teach what is normal, admirable, and manageable long before children encounter policy debates or statistical reports. When typically developing children play with an “autistic” doll that presents autism as self-contained and aesthetically comfortable, they are not learning about the majority of autistic lives. They are absorbing a curated fiction.

At the same time, autistic adults with the highest support needs spend decades isolated from their communities, excluded from services, and absent from public discourse. The contrast is unavoidable.

One group encounters autism as a playful product on a store shelf.

The other lives autism as a lifetime shelved away from society.

Many families, even those as appalled as I over today’s news, have leaned into the hope of good intentions at least. Perhaps the battle-worn years have sharpened my cynicism, but all I see is the nation’s youngest generation being targeted with the same insidious indoctrination we have had to combat for two decades.

Autism is often described as having no single look. That statement is accurate. However, it is applied selectively. When autism is represented publicly, especially for profitability, only one presentation is consistently chosen. It is the sanitized version that reassures the public while absolving systems of responsibility.

If companies truly accepted that autism cannot be reduced to a single presentation, their approach would look markedly different. Real representation would not involve consulting a single organization that primarily represents autistic people who can self-advocate fluently and publicly — the smallest and least structurally vulnerable segment of the autistic population. They would consult multiple organizations across the entire spectrum of autism and include people whose cognitive and medical needs limit their ability to speak for themselves. They would develop customizable representations that reflect variability rather than erase it.

A genuinely representative autism line might include:

multiple body types and ages,

medical and safety accessories,

communication tools beyond a single tablet,

indicators of high support needs,

and representations that do not default to “quirky but capable.”

Such an approach would require confronting disability rather than rebranding it. It would require acknowledging hardships alongside dignity. It would require investment rather than symbolism.

Instead, the public is sold “awareness” products while buying into “acceptance,” and delivered empty aut-washed boxes of inspiration-porn. Multimillion-dollar nonprofits position themselves as the definitive voice for autism while functioning increasingly as marketing partners. Corporations claim goodwill while generating profit, a $165 million boost in two hours today on the NASDAQ, in fact. Society is encouraged by the media to applaud and move on.

This dynamic is not harmless.

Public narratives shape public empathy. Public empathy shapes policy. Policy determines who receives support and who is left behind. This is how record levels of autism awareness coexist with collapsing service systems. This is how families raising individuals with the highest needs are told their realities are too negative. This is how the majority of autistic people disappear from view entirely.

If “inclusion” is to carry any real meaning, it must extend beyond what is marketable. It must account for those whose lives do not fit into branding strategies or feel-good campaigns. Absent that, what is being offered is not inclusion at all, but a curated illusion.

This is not representation.

It is erasure, repackaged.