By: Cristina Gaudio, NCSA Legal & Policy Fellow

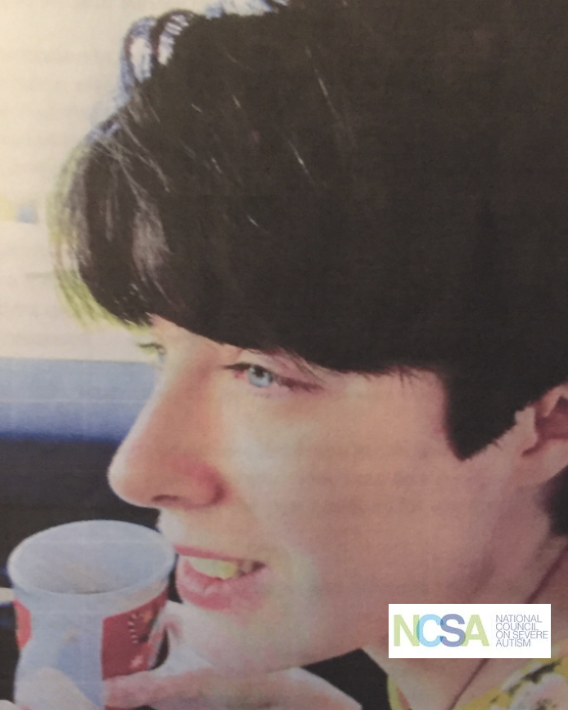

A row of finger-pattern bruises appeared on her arms. Then, an orange-sized hematoma showed up on her leg. Soon afterwards, a mysterious gash required stitches to her scalp. These are just some of the countless suspicious injuries that Caroline Pierce—a severely autistic nonverbal 34-year-old woman—has suffered throughout her time in a Kentucky group home. Ann Jeannette Pierce, Caroline’s mother and fiercest advocate, has demanded answers from Caroline’s residential service provider to no avail. Ann’s requests to install a camera have been denied, her concerns have been largely dismissed, and communications with the investigator initially assigned to her case have been spotty. Caroline’s injuries, according to her service provider’s CEO, are “not atypical,” and she apparently “has suffered no serious injuries” since being placed under the provider’s care. As her family continues to fight these specious claims, Caroline’s story has laid bare a critical policy shortcoming: the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Settings Rule, designed to promote community integration for people with disabilities, has not successfully accounted for the safety and clinical needs of adults with severe autism.

Pursuant to civil rights policy, all people with disabilities, including those with severe autism, are entitled to community integration with appropriate, person-centered support. Caroline is a vibrant woman who, despite her extraordinary support needs, thrives with consistent, attentive care. She enjoys her morning coffee (with ample refills), car rides, and a bubble bath after a long day. Her early care providers understood her needs, and when Caroline was first placed in private care homes, she flourished. Why? Because provider oversight in these settings was characterized by transparency, trust, and common sense. Ann remained heavily involved in her daughter’s care during the early days, collaborating with providers who welcomed her maternal input and daily visits as a means of sensible, appropriate care. Caroline’s support staff read and responded to her aggressive behaviors, recognizing them not as acts to be punished but as communication of want, discomfort, and distress. Most importantly, Caroline, as those close to her are aware, has never been a clumsy individual, and in these care environments, rarely sustained so much as a bruise. Unfortunately, her situation took a turn when the setting of her residence lost its Medicaid backing after being presumed institutional under the CMS Settings Rule, the main provisions of which are found under 42 CFR § 441.530.

Enacted in 2014 under the Obama Administration, the Settings Rule was created to ensure that Medicaid beneficiaries received care in the most community-integrated, home-like settings possible [1]. Since the 1981 addition of §1915(c) to the Social Security Act, Medicaid has been authorized to fund Home and Community-Based Services (HCBS) for people with disabilities as an alternative to traditional institutional care [2]. Via 1915(c) waivers, states fund home and community-based services, which are almost always operated through contracted private providers, in lieu of traditional state-run institutional care settings like Intermediate Care Facilities for Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities (ICF/IID) [3]. The 1999 Supreme Court ruling in Olmstead v. L.C. imposes a civil rights obligation to avoid unnecessary institutionalization for people who met the criteria for institutional level of care. While Olmstead neither bans ICF/IID nor mandates sole reliance on HCBS, it creates legal pressure on states to restructure systems that have traditionally defaulted to ICF/IID models.

Between 1999 and the enactment of the HCBS Settings Rule, states were able to exercise substantial discretion in determining which programs qualified as HCBS for purposes of Medicaid waiver funding. States could designate settings as eligible under HCBS and claim federal matching funds (FMAP) to reimburse the costs of services delivered in those environments [4]. Funding for traditional, ICF/IID—many of which provide 24-hour supervision, specialized medical treatment, and complex behavioral services—has always operated under a separate Medicaid authority from HCBS waivers, although both receive federal funds.

After the 2014 implementation of the HCBS Settings Rule, however, FMAP reimbursement for HCBS became conditioned on new, explicit criteria intended to promote dignity, autonomy, privacy, and community integration. Eligible settings must now, among other requirements, be “integrated in and [supportive of] full access of individuals receiving Medicaid HCBS to the greater community, including opportunities to seek employment and work in competitive integrated settings, engage in community life, control personal resources, and receive services in the community to the same degree as individuals not receiving Medicaid HCBS” [5]. Settings which may previously have qualified as HCBS, like those “providing inpatient treatment; on the grounds of, or immediately adjacent to, a public institution or proximity to institutional campuses,” [6] could now be presumed institutional and made ineligible for reimbursement. Many residential homes, like Caroline’s, were shut down, forcing residents to relocate to settings that were HCBS qualifying. In Caroline’s case, this meant moving to a setting that, while compliant with the rule’s integration criteria, was not designed to meet her level of clinical and behavioral support needs.

Dignified, inclusive treatment is the driving intent behind the Settings Rule, and for many people, states’ program restructuring succeeded in promoting better community access and person-centered decision making. Still, the system has not managed to successfully provide dignified, person-centered care at large for severely autistic people, and the highest support needs remain incompatible with HCBS as it currently exists. Several policy dynamics compound to actively prevent adults like Caroline from receiving appropriate care.

For one, “research suggests tenets of the HCBS Settings Rule, such [as] community integration, employment opportunities, physical environments, educational opportunities, social exclusion, etc., can play a role in either facilitating or hindering people’s quality of life and health” [7]. Criteria like inpatient care, for instance, may be restrictive for people with lower levels of support need. These individuals of course have a right not to be placed in settings with inpatient care. At the same time, inpatient care might be a necessary component of person-centered care for adults with severe autism who require substantial supervision and clinical oversight. These people are entitled to access settings capable of providing this level of care, and under the Settings Rule, this right is being denied. This truth is not an erasure of dignity or autonomy: it is a recognition that safety, clinical support, and structured environments can be prerequisites for inclusion and empowerment. When criteria (like competitive employment and lack of disability-specific campuses) operate as standardized benchmarks with no exceptions, person-centered care is undermined for those where such outcomes are unrealistic and inaccurate measures of a community-integrated, meaningfully engaged life.

Programs that qualify under the new Settings Rule also tend to be small and scattered by design. Unlike state-run ICF/IID facilities, they are built upon a degree of assumed independence and low to medium acuity support needs [8]. While this model presents ongoing challenges even for those it does serve (including workforce instability, inconsistent quality, and limited service availability) its inherent limits on supervision and clinical intensity often make it entirely inaccessible to individuals with severe autism. Because low oversight is baked into HCBS, individuals with severe autism, who often require continuous, 24/7 clinical and behavioral support, may struggle to find HCBS-backed settings capable of meeting their needs.

This exclusion is exacerbated by market-based economic incentives to avoid serving high support needs. Recall that HCBS is almost always administered by private providers. Such privatization of services is not inherently negative; however, the rapidly expanding scale of the industry highlights a need to ensure financial incentives do not come before appropriate care. The disability residential services sector revenue is expected to climb at a CAGR of 2.2% through 2026 to total $42.2 billion by the end of the year [9], reflecting a dynamic where service availability is increasingly shaped, at least in part, by profit incentives. In particular, states often favor privately run services because financial risk shifts away from the ICF/IID government infrastructure. Providers in turn operate with the power to control service capacity. States can cap the number of people served under HCBS waivers, controlling their spend, meanwhile private providers, operating within resource constraints, are practically disincentivized from providing services to those with intensive behavioral and medical needs, as these tend to be the most capital intensive and costly [10]. Without appropriate policy safeguards, these economic dynamics motivate the sidelining of individuals with severe autism.

Ultimately, however, Caroline’s story highlights what is perhaps the most frightening gap within HCBS: that of safety, transparency, and oversight accountability. When suspected abuse occurs in HCBS settings, investigative processes often remain internal to provider organizations. When (to one’s surprise) private providers either fail to investigate or claim no wrongdoing, families are left with limited recourse. Research has established that abuse is disproportionately high among people with disabilities. A Report on the 2012 National Survey on Abuse of People with Disabilities notes that 70% of people with disabilities surveyed had been a victim of abuse and/or bullying [11], with women being more vulnerable to abuse victimization and 41% of people surveyed reporting sexual abuse [12]. These numbers are believed by experts to be understated, as a considerable amount of abuse, especially that of nonverbal women, may not be reported.

Victims and/or their families may reach beyond the provider to report abuse to state health departments, Medicaid agencies, or managed care organizations. However, these actors still operate within the state system that is reliant on private providers to meet demand for disability housing. Facing long waitlists and support professional workforce shortages, states are motivated to maintain existing provider capacity. Respondents are deterred from reporting abuse because there “are too many in the service industry that cover each others’ back if they are from the same agency” [13]. And while loyalty ties between state actors and private providers do not preclude enforcement action per se, they contribute to slower investigations or reluctance to disrupt service availability when allegations of abuse do arise. Among victims who reported their abuse, only 16% said that an investigation was done without delay [14].

Recent news headlines have highlighted how camera technology can bring justice and dignity to autistic people who are unable to testify on their own behalf. In January 2026, a Florida father reported abuse to authorities after noticing injuries to his nonverbal autistic child when picking them up from a group home. Through camera footage, detectives were able to confirm that a group home employee had beaten the victim and thrown them into furniture [15]. In April 2025, the mother of a 19-year-old nonverbal autistic man checked a hidden camera and witnessed his caretaker in the process of sexually assaulting him. She raced home to find the caretaker with her pants still down, and with the footage, was able to press charges in the state of Washington [16].

Nevertheless, Caroline’s story demonstrates how policies that allow for elective video monitoring remain contested under the Settings Rule’s privacy restrictions. Some states, including Kentucky, maintain policies under which state agencies can override a resident or guardian’s request for a camera in an HCBS setting due to privacy concerns. This is what happened in Caroline’s case, and because she is nonverbal, the absence of camera footage has left her family with little means of obtaining clear answers or pursuing accountability. Privacy concerns surrounding electronic monitoring are real, and individuals who do not wish to be recorded should absolutely have the right to decline. At the same time, providers have reputational and legal interests at stake when monitoring is proposed. As such, neither providers nor state agencies alone should have final authority over whether a resident or guardian can install a camera intended to safeguard their well-being. For nonverbal autistic individuals and their families, cameras are not a privacy invasion: they are a lifeline. Effective policy frameworks must recognize these nuances and refrain from imposing blanket camera restrictions in the name of privacy, as these can reduce transparency, facilitate provider cover-ups, and make abuse harder to detect.

Caroline’s story deserves to be shared. She and her family deserve answers, protection, and dignified care. Currently, the Settings Rule and its policy dynamics stand in the way of Caroline receiving these things. Nobody is advocating for a return to the asylums and inhumane institutions of past eras. But right now, HCBS is not delivering on its foundational principles, and a highly vulnerable population is bearing the cost. Recognizing and catering to differences in support needs is not a retreat from inclusion: it is a prerequisite for making inclusion real. Community integration is compatible with accountability, oversight, and clinically intense settings of care when needed. It is time that the Settings Rule is revised so that severely autistic individuals may share in the values it was intended to promote.

Figure 1: A hematoma on Caroline’s leg (photo provided by family; used with permission).

Figure 2: A bleeding laceration on Caroline’s scalp (photo provided by family; used with permission).

Figure 3: A row of pattern bruises on Caroline’s arm (photo provided by family; used with permission).

References:

[1] American Health Care Association/National Center for Assisted Living, “CMS Fully Implements HCBS Final Rule,” AHCA/NCAL Blog, accessed February 10, 2026, https://www.ahcancal.org/News-andCommunications/Blog/Pages/CMS-Fully-Implements-HCBS-Final-Rule-.aspx

[2] Social Security Administration, “Social Security Act §1915,” accessed February 10, 2026, https://www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/ssact/title19/1915.htm

[3] ATI Advisory, HCBS Capacity Building: Provider Development and Workforce Considerations (Washington, DC: ATI Advisory, 2023), accessed February 10, 2026, https://atiadvisory.com/wpcontent/uploads/2022/06/HCBS-Capacity-Building.pdf

[4] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “Financial Management,” Medicaid.gov, accessed February 10, 2026, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/financial-management

[5] Code of Federal Regulations, Title 42, Part 441, Subpart K, “Home and Community-Based Services: Waiver Requirements,” Electronic Code of Federal Regulations, accessed February 10, 2026, https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-42/chapter-IV/subchapter-C/part-441/subpart-K

[6] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Home and Community-Based Services (HCBS) Settings Rule Fact Sheet (Baltimore, MD: CMS, n.d.), accessed February 10, 2026, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/home-community-based-services/downloads/hcbs-setting-factsheet.pdf

[7] Carli Friedman, The Impact of Home and Community Based Settings (HCBS) Final Settings Rule Outcomes on Health and Safety (Towson, MD: The Council on Quality and Leadership, 2020)

[8] Saving Wrentham and Hogan Alliance, Inc., Hidden in Plain Sight: The True Cost of IDD Services in Massachusetts and the Case for Restoring Choice (January 2026).

[9] IBISWorld, “Residential Intellectual Disability Facilities Industry in the US,” IBISWorld, accessed February 10, 2026, https://www.ibisworld.com/united-states/industry/residential-intellectual-disabilityfacilities/1596/

[10] Saving Wrentham and Hogan Alliance, Inc., Hidden in Plain Sight: The True Cost of IDD Services in Massachusetts and the Case for Restoring Choice (January 2026).

[11] Spectrum Institute, Abuse and Neglect of People with Disabilities: A National Survey Report (Los Angeles, CA: Spectrum Institute, 2012), accessed February 10, 2026, https://api.realfile.rtsclients.com/PublicFiles/6c91aefc960e463485b3474662fd7fd2/853d7682-3557-4301- b89a-5d93d7a303c5/ANE-TrainTrainer-2.13.02-NationalSurvey-FullReport.pdf

[12] Yost Law Firm, “Vulnerable Children and Adults in Group Homes Face Risk of Abuse,” Yost Law Firm, accessed February 10, 2026, https://www.yostlaw.com/vulnerable-children-and-adults-in-group-homesface-risk-of-abuse/

[13] Spectrum Institute, Abuse and Neglect of People with Disabilities: A National Survey Report (Los Angeles, CA: Spectrum Institute, 2012), accessed February 10, 2026, https://api.realfile.rtsclients.com/PublicFiles/6c91aefc960e463485b3474662fd7fd2/853d7682-3557-4301- b89a-5d93d7a303c5/ANE-TrainTrainer-2.13.02-NationalSurvey-FullReport.pdf

[14] Spectrum Institute, Abuse and Neglect of People with Disabilities: A National Survey Report (Los Angeles, CA: Spectrum Institute, 2012), accessed February 10, 2026, https://api.realfile.rtsclients.com/PublicFiles/6c91aefc960e463485b3474662fd7fd2/853d7682-3557-4301- b89a-5d93d7a303c5/ANE-TrainTrainer-2.13.02-NationalSurvey-FullReport.pdf

[15] Nancy Gay, “Group Home Employee Accused of Abusing Non-Verbal Autistic Child in Largo,” FOX 13 Tampa Bay, January 22, 2026, https://www.fox13news.com/news/group-home-employee-accused-abusingnon-verbal-autistic-child-largo

[16] AJ Janavel, “Caregiver Charged with Sexually Assaulting Disabled Teen,” FOX 13 Seattle, April 23, 2025, https://www.fox13seattle.com/news/wa-caregiver-charged-sexual-assault

Author’s Note:

Cristina Gaudio is the Legal Policy and Advocacy Fellow at the National Council on Severe Autism. A JD/MPP candidate at Vanderbilt University and a proud autism sibling, Cristina is dedicated to advancing evidence-based policies that support individuals with severe and profound autism. Her work focuses on Medicaid reform, housing access, and meaningful services for profoundly affected individuals. She also serves as a U.S. Air Force Reserve Officer.